Not in my tummy, but in my mind by Vikas Prakash Joshi

It is Newton’s Fifth Law that when a teacher steps out of a primary school class for more than a decent period of time, somebody starts singing or cracking jokes.

The 5th standard class at Diamond International School, Koregaon Park, Pune, was no exception to this eternal rule.

Roshan, or Cinnamon as he was nicknamed by everyone, clutched the long stainless steel ruler like a mike in front of the class. The other twenty students noisily and tunelessly joined in as he belted out Lakdi ki kathi at the top of his voice. It was a welcome break from the Environmental Science Class. Pallavi joined him as the female lead.

Just as the horse was bolting, EVS Ma’am, Mrs. Arora, came back into the classroom.

“Settle down, horses! Roshan and Palli, take your seats,” she said. The class went back to the lesson.

When the class ended, students started filing out noisily.

“Roshan.”

“Yes Ma’am?”

“Where do you stay?”

“Koregaon Park, Ma’am.”

“Wah. You like singing?”

“Ummm…love singing.”

“I am sure even Gulzar in Mumbai would have heard you singing his lyrics.”

“Really, Ma’am?”

“Haanji.”

He blushed and looked down at the ground. It was the first time someone had paid him such a big compliment. He didn’t quite know how to react.

“Thank you Ma’am.”

“How did you get the nickname, Cinnamon? Everyone calls you that.”

“My parents love to add cinnamon to everything. In tea, cakes, pastries and rolls…in everything. I couldn’t pronounce the word Cinnamon so I called it Cimmanum or Cinnamum or even Cimmamom. So they dubbed me ‘Cinnamon’. He frowned. “I don’t like my nickname anymore. I want to change it.”

“Do they like music?”

“No ma’am. They don’t like music…uh…I mean they do like it. But not…er…this kind.” He tried to show with hand gestures what kind he meant.

She gave a knowing smile.

“It’s only me. I don’t know, Ma’am. Maybe my tummy-mummy liked this kind of music.”

“Your tummy mummy?”

“Yes. I am adopted.”

Mrs. Arora fiddled with her dangling silver earrings. After smiling a little too long, she said,

“Ok, wonderful, Roshan. Keep it up. You can go now.”

Baba and Maa had never hid from Cinnamon, or anyone else, that he was adopted. It was as much an accepted part of his life as his alert brown eyes and long, muscular legs.

When he was about two years old, Maa sat him down and told him a beautiful story. She read to him from a slim Bengali book. Cinnamon sat in front of her, curled up on the bed. Baba sat next to her. She told him about the ancient city of Mathura, near Delhi, where Vasudev and Devaki had eight children.

Reading out the story with dramatic voice variations and hand movements, Maa said, “The eighth child was Krishna. When Krishna was born, there was heavy rain. Vasudev took the baby in a wicker basket to the house of Nanda. He placed him with Nanda, a cowherd, for his protection. Lord Krishna grew up with his adoptive parents.”

Baba then told a story in Marathi, in a silky smooth voice. In the story, a charioteer finds a baby in a basket floating in a river. The charioteer and his wife, Adirath and Radha, do not have children of their own. “Little did they know that the boy was the son of princess Kunti and Surya Dev. They named him Karna. He grew up to be a brave and fearless warrior.”

“So, you see, Cinnamon, some children come home in some ways and others in other ways, but every one of them is equally special,” Maa concluded.

Baba said, “When we went to the adoption agency, they said that the boy looks different from you. But that didn’t matter to us.”

When he was four, Baba and Maa took him to the hospital he was born in, in the congested and heaving Kusalkar Road area of Pune. They also took him to the adoption centre, near one of Pune’s biggest hospitals, when he was five, and again when he was six.

Baba told him the story of the day they adopted him. “Cinnamon, the day we went to bring you home, was the most memorable day of my life. It was not only your Maa and me who went to the adoption centre. Ajji, Ajoba, Dada Moshay and Didi Maa also came along. I finally understood what it was like to be the captain of the Indian cricket team. We had only the Maruti Zen at that time, so we arranged two auto rickshaws additionally to take everyone.

He continued, eyes twinkling. “It rained the previous night and early that morning as well and we felt it to be a good omen. Later, we organised a get-together at a small mangal karyalaya for all the people, on your homecoming day. So many people came home, that we had to finally shift it to a much bigger hall nearby.”

Cinnamon asked to hear this several times, and each time Baba added extra details. It was like one of those stories that you never got tired of hearing.

As he grew older, he sometimes stared into the mirror in the bathroom, trying to imagine what his father and mother must have looked like. Did his swarthy skin, impressive height and sharp nose and cheekbones come from his father? Did he get his loud laughter and voice from his mother? Where did they live and what did they do? When he travelled anywhere, he looked around at people, wondering whether any one of them was his father or mother.

Baba and Maa always supported him and let everyone know that he was adopted, so he had no sense of shame or embarrassment. He saw it as a very natural part of his identity.

On one occasion, when he was about six years old, he asked Baba, “Baba, if my birth mother were to come and ask to take me back, what would you do?”

“We don’t know where she is and she doesn’t know where we are either. So that can’t happen. Moreover, we love you and we won’t let you go ever.”

Later, when he was around seven, he had more questions.

He asked his parents, “What did my birth father and mother look like? Are they tall like me?”

“We don’t know, Cinnamon,” they said patiently.

“How come?”

“We have never met them.”

“Why did they leave me? How could they do that?” He cried out.

Baba and Maa hugged him tightly and kissed him. “Was there something wrong with me?” he persisted.

“They didn’t give you up. There was, and is, nothing wrong with you. Your birth parents must have had some very good reasons, that is why they had to take the decision they did.”

But somewhere it remained in his mind. Why did they let him go, Cinnamon thought?

On the first floor of their building lived Nivedita Tai and Yatin Dada. They were regulars at the jogging track with Baba. They often came back home together, drenched in sweat, with Yatin and Nivedita always laughing, and Baba recounting some story or the other.

One day, at the breakfast table, Maa told Baba with a smile, “You know, Nivedita is expecting.”

Baba chuckled. “Well, that was quick,” he said.

Cinnamon didn’t know what Nivedita was expecting but he did see Nivedita Tai’s otherwise flat stomach grow and grow with no end in sight. It troubled him but nobody was bothered about it. On the contrary, they all seemed very happy. They even patted her on the stomach.

He asked Maa, “Maa, what’s happening to Nivedita Tai? Why doesn’t she do something? She will burst open!”

“Khoka, she will do something soon.”

Then, one day, Nivedita Tai suddenly disappeared and so did Yatin Dada. Their flat was locked.

After a week, the doorbell rang. It was Yatin with a box of golden kesari pedhas in his hands. He was beaming as if he had won on Kaun Banega Crorepati or become the Prime Minister of India.

Maa came up to the door. “Oho! Congratulations!” exclaimed Maa, and hugged him. Baba reached out and hugged him too.

“What is her name?”

“Anvee.”

“Beautiful name. Welcome to the club, sir. Congratulations,” Baba said in Marathi.

Cinnamon didn’t completely understand why Baba was congratulating Yatin if Anvee had come out of Nivedita Tai’s tummy. What did he have to do with it, Cinnamon wondered.

On many Sunday evenings, she invariably gave a head massage to Cinnamon, with mustard oil. Baba had tried to get her to switch to coconut oil, but to no avail. Though Cinnamon hated the smell, he always loved the warm and fuzzy sensation it left when she finished her massage.

He sat on a newspaper on the floor, while she vigorously pummelled and pounded his head.

“Head massage is good for blood flow and intelligence, you know,” she declared. “Your Dadu and Didima gave us regular head massages and castor oil, when we were growing up. That’s why we turned out so well, I say. It’s a must actually, for all children.”

Cinnamon knew where this conversation was going, so he decided to divert it.

“Maa, I have a question,” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Anvee came out of Nivedita Tai’s tummy?”

“Of course, baby.”

“So you and Baba also came out of Didima and Ajji’s tummies? And others too?”

“Yes, even we did,” she reassured.

“But I didn’t come out of here?” He turned to touch Maa’s tummy. “I wasn’t in here?”

“Not from my tummy. You were in my mind,” she said in Bengali, quoting Tagore.

“Whose stomach did I come from?”

“Your birth mother’s.”

He looked at his own tummy and imagined a baby inside. He imagined himself inside a tummy, arms and legs and all. What an ugly sight it must have been.

“Maa, it must be so painful,” Cinnamon cried out.

“Yes, it is painful at that time but then once the baby is born, the pain goes.” He considered this for a moment.

“Don’t you think that shows how nice I am? I came without causing you any trouble.” Maa cupped his chin and laughed.

Then she carried on with the head massage, humming to herself.

--------------------------

* "The above excerpt (or extract) has been taken from Vikas's forthcoming novel My Name is Cinnamon.

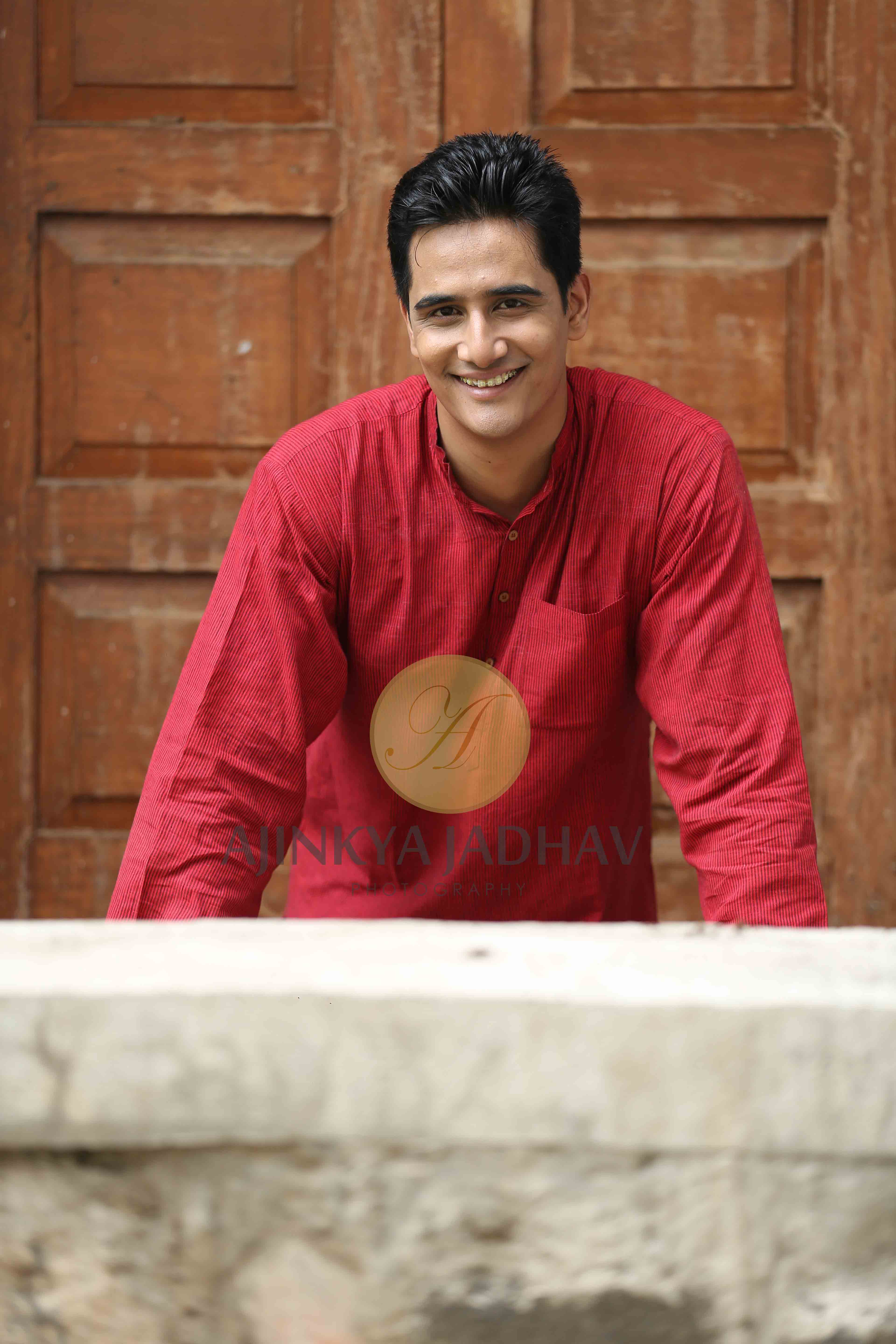

* About the Author

Vikas Prakash Joshi, an Indian by nationality, is a writer by ‘nature’, not by choice, coincidence or compulsion. He was born and lives in the city of Pune, in western India, known for its rich cultural traditions. His writing career started in school and college at 13 where his contributions were published in the school newsletters and he won prizes in essay competitions at school level. He wrote over 150 letters to prominent English newspapers in classes 9 and 10, winning five ‘letter of the week’ contests in leading newspapers and magazines before becoming a newspaper columnist in a major newspaper at the age of just 18. His columns and short stories thus reached tens of thousands of readers. He subsequently won awards in city, state, national and then international-level writing essay contests. His articles and stories have been translated into 10 languages: Hindi, Gujarati, Marathi, German, Sinhalese, Bengali, Greek, Italian, Russian and Serbian, and more are on the way. He has been published in India, New Zealand, Belgium, Italy, Germany, Greece and Romania.

He has a B.A. in English Literature from the Symbiosis College of Arts and Commerce, a postgraduate diploma in journalism from the Asian College of Journalism, Chennai (where he received the Madanjeet Singh South Asia Foundation Scholarship) and an MA in Development Studies from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. He has written for leading Indian publications like Caravan, The Wire, The Hindu, DNA, and reported from very diverse parts of India, from metropolitan cities like Pune and Bangalore, to the small, rustic villages.

You can reach Vikas at joshi.vikas500@gmail.com

0 تعليقات