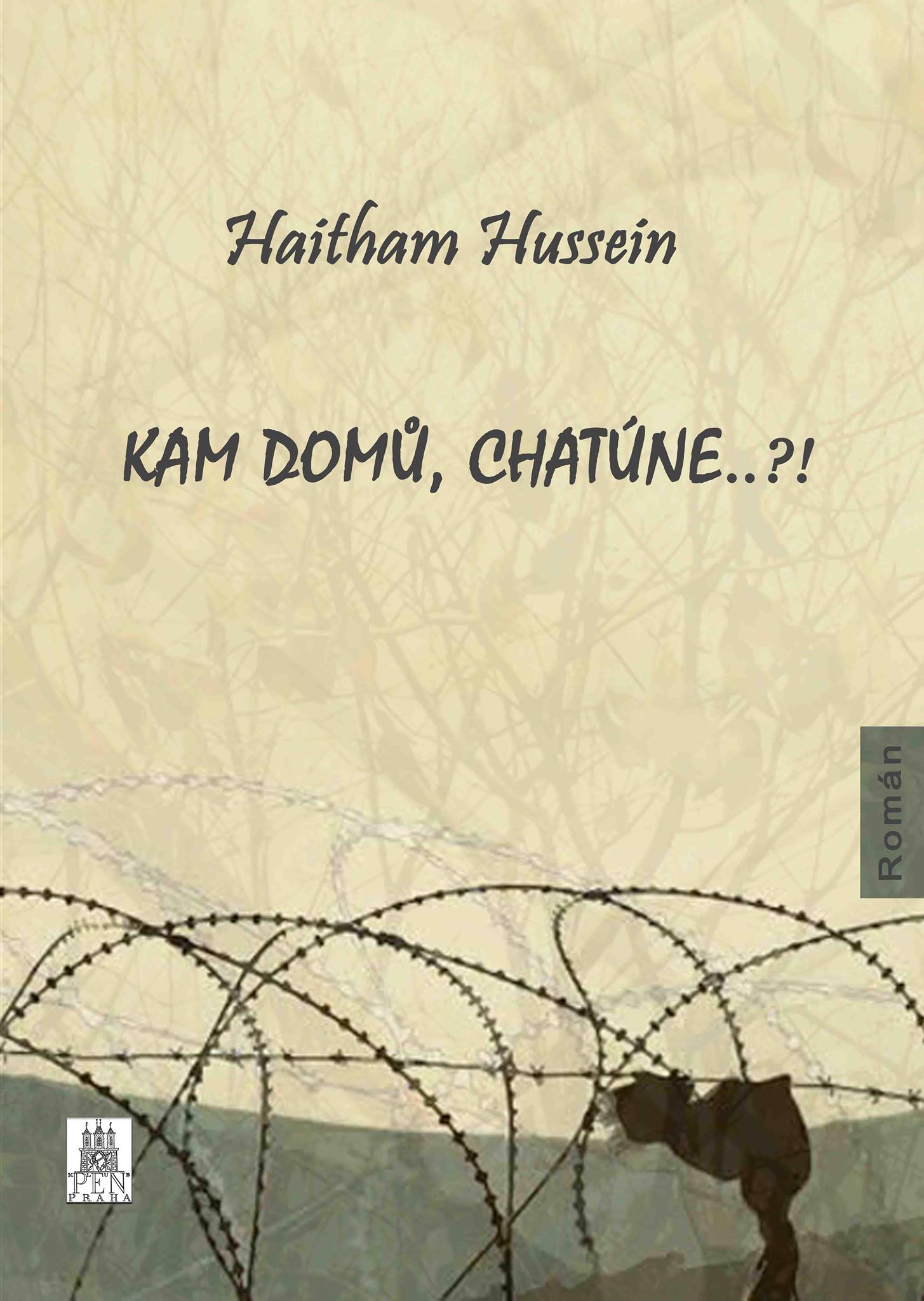

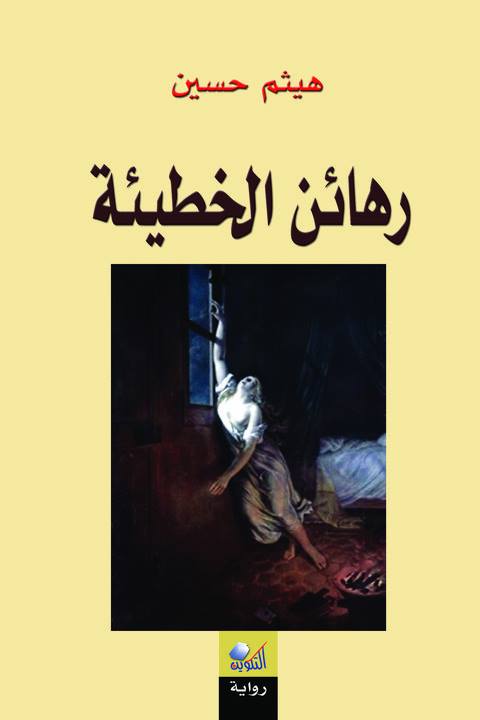

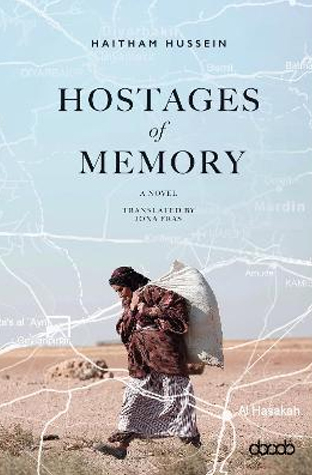

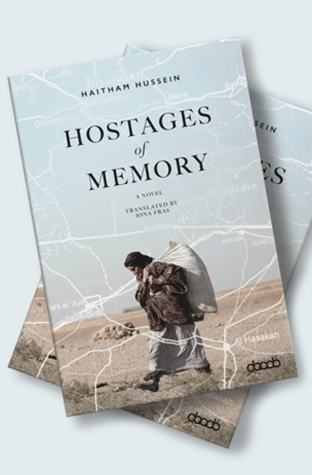

Hostages of Memory by Haitham Hussein - translated by Jona Fras

“Hostages of Memory”

by Haitham Hussein – translated by Jona Fras

Hostages of Memory (Arabic title:رهائن الخطيئة ) was initially published in Syria in 2009, has been translated into Czech (2016), and is currently being translated into French.

The novel chronicles the story of a Kurdish woman, Khatouna, and her two sons, Alo and Ahme, as they move through villages in the Turkish-Syrian borderlands in the 1960s, fleeing from the consequences of an event in Khatouna’s past which she stubbornly keeps secret. The family comes to settle in the town of Amouda, in Syria, and though viewed suspiciously by the locals at first, Khatouna and her boys manage to build a life for themselves, lifting themselves from extreme poverty into something resembling a dignified existence. A series of family fortunes and misfortunes follows, during which the reader finally comes to learn the truth regarding the crime which forced Khatouna to flee her home and become a refugee in her own land.

Through its Kurdish characters, Hostages of Memory offers the reader a unique glimpse into the extremely complex social fabric of North-Eastern Syria, and issues of identity and history woven through life in this borderland region. It is also, however, a novel about family; the importance of blood ties in the face of adversity; and a subtle mystery which draws the reader to find out why, precisely, Khatouna and her boys would come to live as they did.

Chapter 3

Grandma Khatouna would break stale bread into pieces and put it into canvas bags to sell later. This was how she’d remind herself of her past life, when she used to wander from village to village in the lands known as Jayaye Omriyan. There wasn’t a single village she hadn’t visited; and while she did come to know quite a few people in each of them, she never seemed to be able to settle down. She was always on the move, as if there was a crime pursuing her that she never could quite flee from, or a sin she hadn’t received forgiveness for. She did, finally, come to settle down in Amouda, where she contented herself with a hut on the outskirts of town. Her children stayed with her, two boys barely a few years of age, and a black goat that was never tied up and during the night slept with them in the hut.

She was cautious towards everyone at the beginning. Whenever someone approached her house she would draw herself back, and ask them sharply after their business before they could step closer. Gradually, once she’d reassured herself that the locals only wanted to help her – to learn her story, do her a favour or two, perhaps discover some distant relation of hers – she came to trust them more. But she did not throw herself blindly into their graces. She ignored most of their offers, and would shut every door that might have been opened regarding the village she’d come from, or her family or relatives. “From the broad lands of God,” was all she had to say. Sometimes, she’d be a little more specific, though only by repeating something everyone already knew: that she was from “above the line.” And that, really, was the end of it.

People grew to accept this, and would no longer ask her about it – except occasionally. So she came to be known as Khatouna of Jayaye.

She experienced her share of calamity and misfortune during her first twenty-five years in the town. She would sew bedcovers and raise cows to provide for her little family. She also worked as midwife, and didn’t much care about what she would sometimes hear from this or that woman whom she’d helped deliver: that she was heartless, that she was never stirred by their screams or cries for help during labour – as if she hadn’t delivered her two sons herself, or had never experienced the iron-melting pains of childbirth. She would comment only that it was her duty to do as she did, for the new mothers’ sake. Labour wasn’t a time to feel for others; it would only cause harm.

Her sons grew up working as delivery boys in the market. They both wore woolen skullcaps and prayed dutifully at the mosque every Friday. People came to like them, and as the years passed they would no longer ask them about why they’d come to Amouda, or any other of Grandma Khatouna’s many secrets – which looked as if she would take them to her grave, and never relieve her soul of the pain of suppressing them. She wouldn’t reveal them to anyone, not even her boys, no matter how much they begged her to do so. She never told them even a single word more than what she told everyone else. So they were forced to accept her silence, and – like everyone else – stopped asking her about it. Still, it gnawed at them, from time to time.

Sufi Alo reached and passed thirty without once broaching the subject of marriage with his mother, or his brother for that matter. He knew very well how pitiful their circumstances were, even as he and his brother advanced from delivery boys to street peddlers to partners in a small store on the Arasa Market. But then there came the day when Sufi Farho told Alo to wait for him at the gate of the mosque after evening prayers, and asked him to marry his daughter.

The women called this daughter of Farho’s “Shekrawka Karrik,” meaning she was half-deaf. Sufi Farho’s offer to Sufi Alo came on the basis of their shared religious devotion, and because Alo had proven his good nature and excellent morals, and also because Alo was a capable worker and Farho wouldn’t have to worry about his daughter if she was married to him. He hastened to add that he would, of course, help Alo cover some of the wedding expenses. He wouldn’t ask for a bride-price either; Alo upholding his promise and taking care of his daughter would be bride-price enough.

Alo, more than a little stunned, accepted Farho’s offer there and then. He swore he would never lay his eyes off Farho’s daughter, and never make her want for anything. He did not care if his betrothed was old or deaf, or that Sufi Farho may have approached him as a last resort for a daughter whose hand had never been asked for and who had lost all hope of marrying. For Alo, to become a son-in-law to someone like Farho had never been anything more than a distant dream – and yet, here he was now, on the verge of this dream becoming reality.

They both had supernatural explanations ready to account for their good fortune. Alo liked to think it was God’s own unadulterated love that chose him from among so many others. Farho, outwardly, ascribed it to fate, and kept for himself the true reasons that had forced him to make his proposal.

But the new groom did not care to look for these reasons; nor did Grandma Khatouna. The marriage was the right way forward. This they knew, or at least convinced themselves of it.

Chapter 4

After Sufi Farho had made Alo burst with joy over tidings he’d never dared to dream of hearing, he added a comment. Just a small one; but he was obliged to mention it, he said. His daughter had a “hearing problem.”

Alo didn’t quite know how to respond to Sufi Farho’s overflowing generosity, and his sincerity embarrassed him. He had little to say other than that of course he did not attach any sort of importance to the issue of hearing problems. And so it was – even later on, when the “hearing problem” really turned out to be almost complete deafness, one with which no amount of shouting did any good. You had to use hand gestures, or yell loudly enough that all the neighbours would hear. But Alo was happy to live a quiet life, without all the likely annoyances his wife might have brought him with gossip and prattling.

And so was she. Her deafness, and her father’s cruelty, had imposed a total silence upon her life. She lived isolated from everything, her world confined to the demands of housework and motherhood. As for her conjugal duties, they soon virtually disappeared; she got used to ignoring and suppressing her own desires, like most other women she knew, and only responded to those of her husband, even as these grew less and less frequent as time went on.

She’d lost her hearing more than twenty years ago, when she was still a child. She was sweeping the front door on a summer evening, a little before sunset, with a bit of water splashed on the floor so she wouldn’t raise dust – when she suddenly caught sight her father, marching swiftly towards home, returning early from the market. Farho was shouting and cursing at her, and when he came near he punched her so strongly she fell down and hit her head on the wall behind her. He then ordered her to get inside the house, with another stream of curses, and swore by God that he would murder her if he saw her sweeping the front door ever again.

This monstrous behaviour of Sufi Farho’s has another story behind it, which can be told here in brief. When he was in the market that day after the afternoon prayers, he happened to overhear a conversation among a group of delivery boys – whom he would later describe as filthy and depraved – sipping their tea and exchanging whispered remarks about the guiles and artifices of women.

These were men well-versed in sowing mistrust and spinning tales that revealed people to be malicious and wicked, even if they appeared innocent. A girl might, for example, use the excuse of sweeping the front door in order to go outside at a particular time agreed with their lover. She would take her time sweeping and standing until her lover came by and saw her or spoke to her in order to arrange another meeting; and this would, later on, lead to disaster and tragedy, when the lovers met somewhere far from the eyes of the people, and the man would take what he wanted from her and then cast her aside like a wet rag…

Before Sufi Farho could fully absorb the ravaging shockwaves of what he had just heard, another of the delivery boys interjected that one should get rid of such a girl immediately by marrying her off as soon as the “sieve passes between her legs,” that is as soon as she matures. “Wean her off the tit and find her something harder to suck on,” he added, to general laughter; it was more than clear what he was referring to.

These warnings echoed in Farho Tawtus’ ears, and doubt began to creep over him. He hadn’t been able to find a match for his daughter, and so, slowly, his suspicions grew. They’re right, he told himself. They have to be.

He rushed home for sunset prayer, aching to empty his bladder but forced to wait until after prayer unless he wanted to invalidate the ablutions he’d taken such pains to perform earlier that day. When he spotted his daughter sweeping the front door of the house without a veil on, he was immediately convinced the delivery boys had spoken the truth. Rage and jealousy overcame him, and so he did what he did. While his daughter still considered herself a child, her father and everyone else regarded girls of her age as already quite mature, with honour that had to be protected. So she became a victim of her own naïve good opinion of herself – or rather, the mistrust of her father. She was considered mature, and on this basis she was judged.

The incident rescued those around her from the tumult she would likely have caused, and rescued her from the tumult that would have been caused by those around her. Farho, however, would never again be at peace, and would never stop asking God’s forgiveness for his suspicions about his daughter. He tried to atone for his actions by spoiling her, by being nice to her, by speaking to her gently and sparing her work and generally asking less from her. And yet she was punished if she spoke up, and left in pain if she remained silent. She was only ever happy when she was doing housework. She remained scrupulous and reliable in all she did, and kept her honour intact.

But Farho’s punch had already tainted her inexorably. Suspicions swirled around her, and malicious gossip that only cared about what it wanted to find, no matter how convincing other answers might have been. Farho chastised himself over and over again for using violence when he shouldn’t have. Still, his madness and rashness and blind jealousy had kindled the fire, and no amount of remorse on his part could put it out. The genie of speculation and slander was out of its bottle; and, as the proverb says, vicious tongues are hardly like a belt that one can tighten or loosen whenever one wants.

0 تعليقات